The revolt of the farmers in the last decades of the 19th century — which spread quickly across the entire South, West, and Midwest of the United States and resulted in the formation of the radical Farmers’ Alliance followed by the Populist Party — was the largest third party movement in U.S. history. The best book on the subject is still the 1931 classic by John D. Hicks, The Populist Revolt. It is a thorough and well-written history of the movement. The first chapter, which describes the frontier background of the story in an unusually clear-eyed description of the buying and selling of the West, is worth reading on its own. And the last chapter of the book, on the many Populists’ demands for reform that were eventually adopted as government policy, is also worth reading on its own.

[The book’s first and last chapters can be read here. A bibliography of works relevant to the populist revolt, including articles by Hicks, is included here and at the bottom of this page.]

Who were the Populists and what did they do?

The last chapter of The Populist Revolt begins with a quote from a Populist newspaper claiming that “the cranks always win”:

The cranks are those who do not accept the existing order of things, and propose to change them. The existing order of things is always accepted by the majority, therefore the cranks are always in the minority. They are always progressive thinkers and always in advance of their time, and they always win. Called fanatics and fools at first, they are sometimes persecuted and abused. But their reforms are generally righteous, and time, reason, and argument bring men to their side. Abused and ridiculed, then tolerated, then respectfully given a hearing, then supported. This has been the gauntlet that all great reforms and reformers have run, from Galileo to John Brown.

—from The Farmers’ Alliance, February 15, 1890, a weekly newspaper published by the Nebraska State Alliance.

Hicks then says that while “The writer of this editorial may have overstated his case, a backward glance at the history of Populism shows that many of the reforms that the Populists demanded, while despised and rejected for a season, won triumphantly in the end” (404). In the rest of the chapter (Chapter 15), Hicks surveys the Populists’ proposed reforms that were eventually enacted, arguing that although the movement collapsed after 1896, its influence on later movements and on the eventual policies adopted in response to that influence was significant.

Hicks begins the chapter by making the interesting point that the Populists’ proposed reforms were based on the assumption that the ordinary American worker should be able to expect not just the chance to work but also a degree of prosperity. When farmers across the midwest and west found themselves without work or, having work, still unable to pay their debts, in the lean years of the 1880s and 90s, they felt that there was something wrong somewhere, and soon fixed the blame on the railroads, manufacturers, moneylenders and middlemen – the “plutocrats,” who had all gotten richer as the farmers got poorer.

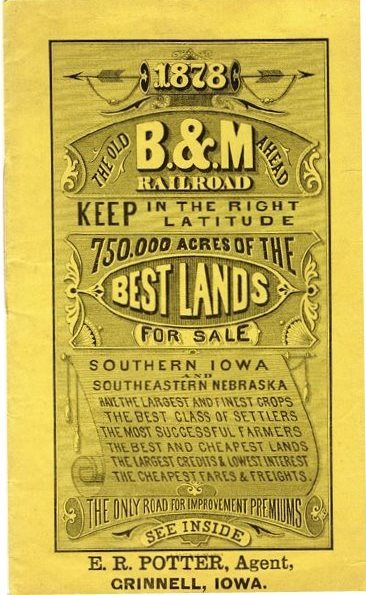

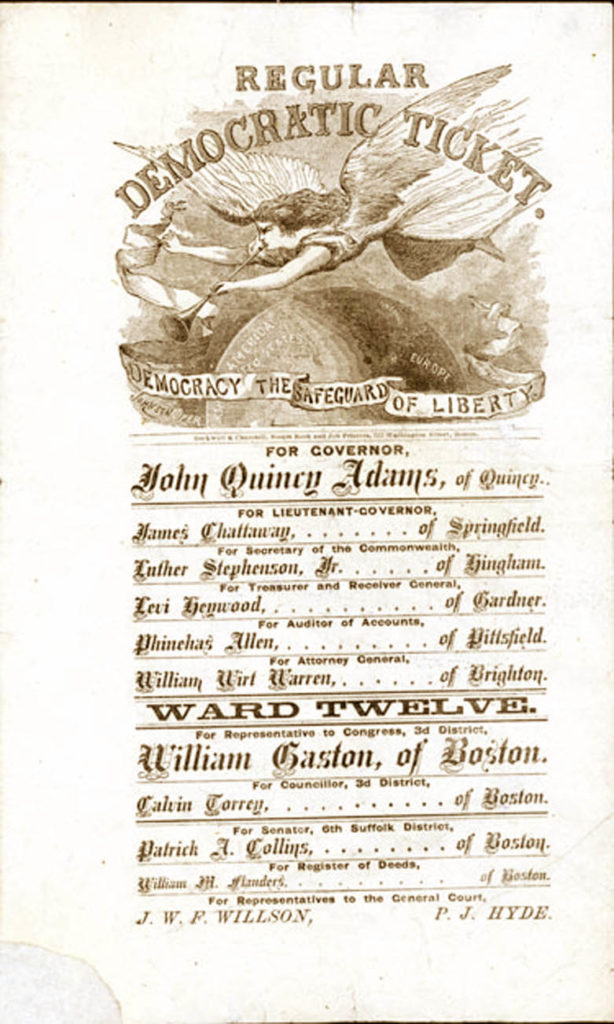

In his analysis, Hicks then makes a nod to Frederick Jackson Turner: in the past, he says, farmers and laborers could flee to free farms in the West in bad times, but now the free lands were gone, and they turned to legislation for a solution to their problems instead – “from the ideal of individualism to the ideal of social control through regulation by law” (405) But the government was controlled by the plutocrats. First the people needed to gain back control the government. And for this, they advocated, along with many other reformers of the time, the adoption of the “Australian” secret ballot (our current system), women’s suffrage, and the direct election of the president, vice president, and senators, for, as they viewed it, “the voice of the people was the will of God.” Direct election of senators was an issue that was especially identified with Populists.

Another Populist issue, one that governments began adopting even before the Populist movement faded, was the direct primary. Previously, a party’s nominees in an election were chosen, usually by party bosses, at the party’s nominating convention. This of course also lent itself to control by corporations and “plutocrats” as it is easy to bribe a few officials to get what you want. With a direct primary, the people chose a party’s candidates, taking it out of the hands of the few, putting it in the hands of the many. The secret ballot and direct election of senators and party nominees are now standard features of American politics. Here the Populists won hands down.

For some, the signature issue of Populism is the initiative and referendum (I & R). It is probably the issue the Populists were most passionate about. They started advocating for initiative and referendum early on and the states in which it was eventually adopted were mainly those in which Populism had been strong. For those unfamiliar with the concept – perhaps because they live in states without initiative and referendum – at least the first part, referendum, should be familiar. In most states, there are issues on the ballot to vote for as well as candidates running for office. But if citizens do not have the initiative in that states, the ballot issues are chosen and put on the ballot by the legislature – the citizens do not have a direct say in this. But when a state has initiative and referendum, the citizens themselves can put issues on the ballot, usually by circulating petitions calling for a particular issue to be voted on and getting a sufficient number of signatures. In this way, the citizens themselves choose what issues go on the ballot.

It needs to be noted that this method of creating legislation does not replace the state legislature or executive or courts, but simply adds one more variable to the mix. State legislatures may modify the results of a citizen initiated referendum, though usually with certain restraints, and the courts will certainly have their say. How this works out in practice varies from state to state. In California and Oregon, an issue voted in by the citizens can only be replaced by another citizen-initiated referendum. In other states, it requires a super-majority in the legislature for the legislature to modify or overturn it, and in still others, a simple majority in the legislature can negate a citizen’s law. A final feature, often accompanying initiative and referendum, is recall. There, an elected official, or even an appointed ones, including judges, can be removed from office by again circulating a petition, getting sufficient number of signatures, and having an election. If the target of the recall is sufficiently unpopular and the vote goes against them, they lose their job. Together these are referred to as initiative, referendum, and recall.

After running through the changes in our form of government that the Populists can take much credit for, Hicks then makes another interesting point, that “the Populist propaganda in favor of independent voting did much to undermine the intense party loyalties that had followed in the wake of the Civil War” (409). To people today, this might seem like a dubious claim – when we look back, we see the “solid South” running throughout the 20th century right up to the Republican Party’s “Southern Strategy, which began in the 1960s and that hardly looks like independent voting to us, but is rather entirely dependent on one political party or another. But Hicks wrote in the late 1920s and early 1930s, publishing his book in 1931, and from his perspective, when the nation was still in the process of breaking free from mindsets entirely determined by the Civil War, he may have been comparing his times with what he could see was a ferociously fixed Civil War perspective, and compared to that, people were more independent politically after the Populist movement.

Recall, though, that turning control of the government over to the people was just the first step for the Populists. As Hicks puts it: “The control of the government by the people was to the thoughtful Populist merely a means to an end. The next step was to use the power of the government to check the iniquities of the plutocrats” (412). Here, then, economic issues took over – again, often with significant influence on future government policies. These issues concerned the currency, banking, loans to farmers specifically, railroads and the monopolistic hold they had of the farmers in the West and on state governments, and monopolies in general.

The Populists were especially ridiculed for their views on currency. These they inherited from their predecessors, the Greenback Party. (Many Populists had been Greenbackers prior to joining the Populists.) Essentially, the supply of money in the U.S. was not growing because it was required that every dollar be backed by gold, and the supply of gold was not increasing very fast. Thus, post-civil War America experienced a steady deflation – as the economy expanded while the supply of money did not, the dollar became worth more and more. So people who had dollars became richer and richer as their dollars became worth more, while people who owed money – including most farmers, became poorer and poorer as they were required to repay their loans with more and more valuable dollars. The Populists, then, like the Greenbackers, favored expanding the currency, first, by allowing dollars to be backed by silver in addition to gold, but ultimately by having the government simply print dollars as needed to match the expanding economy with those dollars being backed by nothing at all. As mentioned, the Populists were soundly ridiculed for this view – probably because the idea that people held of money having value was intimately associated in their minds it being redeemable for gold. But the government’s monetary policies gradually moved closer and closer to the Populists’ views until, in 1971, the U.S. government finally renounced the gold standard and dollar bills were not backed by anything at all.

The most important issue to the Midwestern farmers was the railroads and the monopolistic hold that they held for shipping farm produce to the central markets in Chicago. The Populists demanded government regulation of railroads and all means of communication, which they eventually won, but further, they demanded government ownership of railroads and means of communication, which has not been won. They were less clear in their objections to monopolies in general and had no specific solution to the problem except their support of anti-trust laws.

There were many other minor or more specific policies advocated by the populists that were later enacted, but just from these are the broad outlines of their influence, and it can be seen that the Populists, rather than being the backward-looking defenders of a disappearing small-town system of values, as has been argued by some, were instead constructive activists of what the modern age should be.

Works by John D. Hicks

The Populist Revolt: A History of the Farmers’ Alliance and the People’s Party, University of Minnesota Press, 1931. Reprinted as a Bison Book, University of Nebraska Press, 1961.

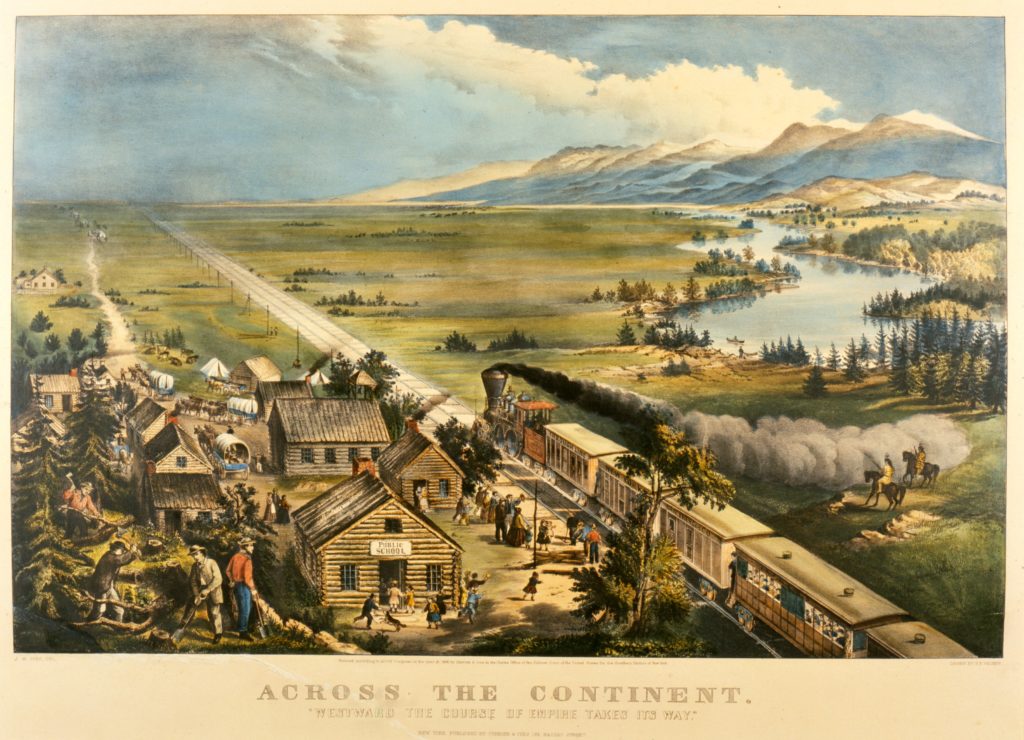

“The Frontier Background,” Chapter 1, The Populist Revolt, 1931. Hicks opens his book with the story of the buying and selling of the West, told vividly, and in detail.

“The Populist Contribution,” Chapter 15, The Populist Revolt, 1931. In the last chapter of The Populist Revolt, Hicks surveys the reforms advocated by the Populists that were later enacted.

“The Legacy of Populism in the Western Middle West,” Agricultural History vol. 23, no. 4 (October 1949), 225-236

“The American Tradition of Democracy,” Utah Historical Quarterly vol. 21, no. 1 (January 1953), 25-41

“The Western Middle West, 1900-1914,” Agricultural History vol. 20, no. 2 (April 1946), 65-77

“The Third Party Tradition in American Politics,” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review vol. 20, no. 1 (June 1933), 3-28

“The Birth of the Populist Party,” Minnesota History vol. 9, no. 3 (September 1928), 219-247

“The Persistence of Populism,” Minnesota History vol. 12, no. 1 (March 1931), 3-20

“The Farmers’ Alliance,” with John D. Barnhart, The North Carolina Historical Review vol. 6, no. 3 (July 1929), 254-280

“Our Pioneer Heritage: A Reconsideration,” Prairie Schooner vol. 30, no. 4 (Winter 1956), 359-361